Casey liked to play it safe. If Riley wore green sneakers, Casey bought the same pair. If Riley was into a new playlist, Casey added every track. Even jokes traveled from Riley’s mouth to Casey’s, word for word. It wasn’t mean or sneaky; copying just felt easier than choosing.

On Monday, Ms. Kim announced a project. “Create a two-page zine on anything you care about,” she said. “A zine is like a mini-magazine you make yourself—it can have words, drawings, photos, or anything you want. You’ll present on Friday.”

After class, Riley’s eyes lit up. “I’m doing ‘City at Night’—short poems and photos. Streetlights look like stars.”

Casey nodded. “Great. I’ll do ‘City at Night,’ too.”

Riley laughed, thinking it was a joke. “No, seriously. What’s your angle?”

Casey shrugged. “Same as yours, probably.”

All week, they worked at the same table. Riley arranged pictures of glowing windows and wrote tiny poems in the margins. Casey watched and waited. If Riley used a bold title, Casey used a bolder one. If Riley drew a skyline, Casey added a skyline with a bridge. It looked impressive, but it didn’t sound like Casey at all.

Midweek, Ms. Kim stopped by. “Tell me about your ideas.”

Riley pointed to a page. “I’m trying to show how the city feels alive after dark.”

Ms. Kim turned to Casey. “And you?”

Casey swallowed. “I meant to do that, too. Like—similar. But different.”

“How?” Ms. Kim asked.

Casey stared at the page. “I don’t know yet.”

By Thursday night, nerves kicked in. Casey flipped through the zine. Everything was polished, but nothing felt personal. It was like wearing Riley’s shoes and hoping they fit.

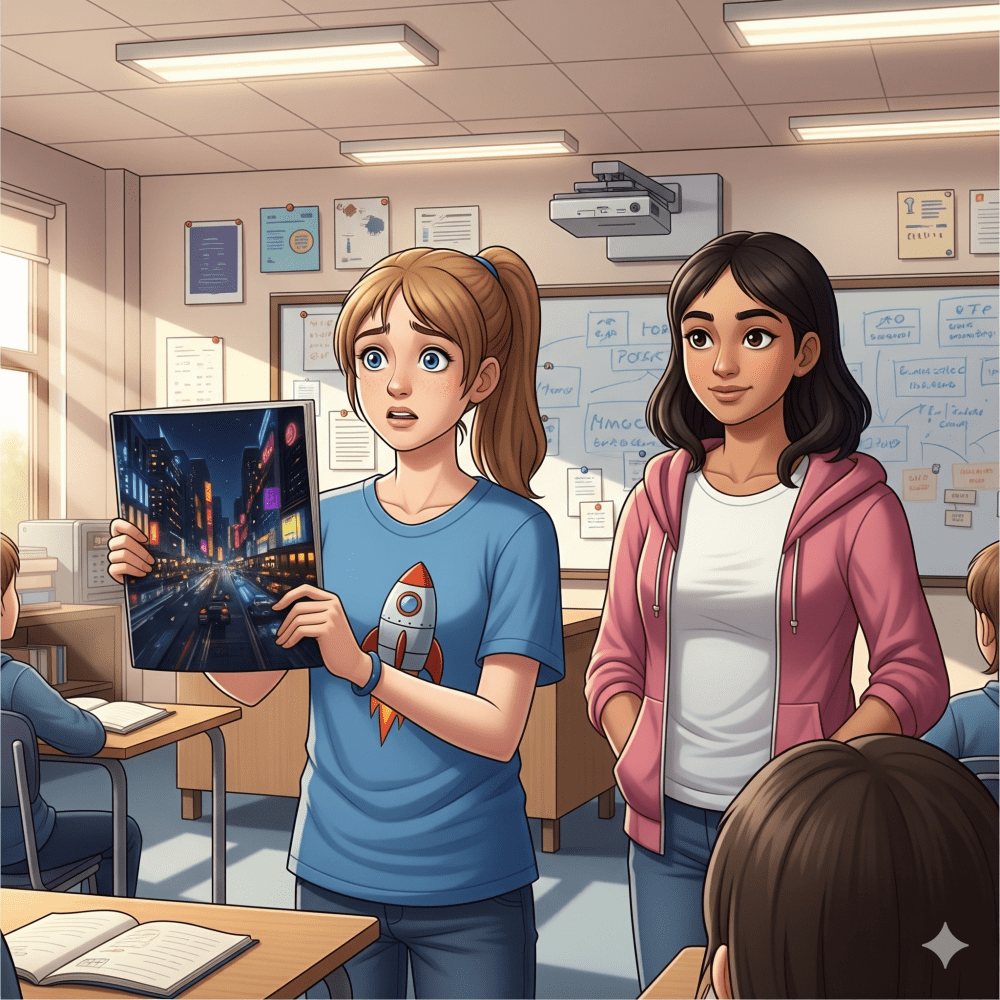

Friday arrived. The class settled, and Ms. Kim called, “Riley and Casey.”

Riley whispered, “You start.”

Casey stepped forward and held up the zine. “My project is called ‘City at Night.’ It’s about how the city, um, glows.” The words sounded borrowed. A few classmates shifted in their seats.

Ms. Kim tilted her head. “Casey, why did you choose this topic?”

Heat rose to Casey’s face. The truth tumbled out. “Because Riley chose it. I didn’t want to mess up, so I copied. I always do. It’s easier to be second than wrong.”

The room went quiet. Riley’s expression softened, surprised but not angry.

Ms. Kim nodded slowly. “Thank you for being honest. Being inspired is normal. But a zine works best when it sounds like you.” She tapped Casey’s empty back page. “You have five minutes. Write something only you could write. One paragraph. One sketch. Anything.”

Casey sat, heart pounding. Write something only you could write. What did Casey actually care about? Not city skylines, not streetlights. The answer popped up, small and clear: the bus stop on Maple, where Casey waited every morning with a cold backpack strap and a warm bagel tucked in a pocket. The slanted bench. The neighbor’s orange cat. The coach who nodded without talking. The tiny routines that made the day feel steady.

Casey scribbled:

“Maple at 7:14”

The bench leans left like it’s listening. The orange cat checks us in, tail up. The bus sighs before the doors fold open. I count seven gum spots, every day. When the sun hits the cracked sidewalk, it looks like a map only I can read.

A quick pencil sketch followed: the bent bench, the cat, the little circles of gum like stars.

Time. Casey walked back up and read the paragraph. It wasn’t fancy. But the words felt real, like speaking in a voice that had finally shown up.

Riley smiled. “That sounds like you.”

Ms. Kim’s eyes warmed. “Now I know your angle.”

After class, Riley bumped Casey’s shoulder. “For what it’s worth, I want a copy of Maple at 7:14 for my wall.”

Casey grinned. “Deal. And next time, I’ll start with my own idea. Even if it’s weird.”

“That’s the point,” Riley said. “Weird is how people remember you.”

On the bus home, Casey opened a notes app and typed: ideas—things only I notice. The list grew: the squeaky locker, the smell of pencils after sharpening, the way Grandma’s porch light clicked once before it stayed on.

It wasn’t a plan for every project. But it was a start. And for the first time, being original felt less scary than being second.

“Copycat Casey” by Nina D. Smith. Published by Bright Bunny Books © 2025. Retelling of “The Unoriginal Boy” from The Parkhurst Boys and Other Stories of School Life by Talbot Baines Reed, originally published in 1914.

“Copycat Casey” is best suited for grades 6–8 because it explores creativity, peer influence, and identity—key themes that resonate with middle schoolers learning to express themselves and develop their own voices.

Discussion Questions

- Why do you think Casey found it easier to copy Riley instead of coming up with an original idea

- How did Ms. Kim encourage Casey to discover something personal to share?

- What are some ways you can show originality in school or daily life, even if it feels risky?

This content is provided under fair use for educational purposes only. Commercial use is strictly prohibited by the creator.